More Information About the Credit Card and Brenda L.

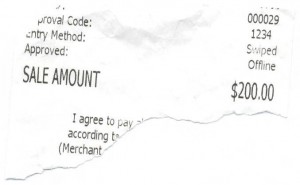

A closer look at the scrap of $200.00 receipt shows the word “Offline.”

Since Lakewood had only been accepting credit cards for around two months, the recorder was still becoming familiar with the information printed on a receipt. She contacted the processing bank. For this transaction, the then-court clerk tried to swipe a credit card, but it was declined. She knew enough about processing credit cards to force a charge to go through, which caused the receipt that she needed to print. After she printed the receipt, she immediately ran a $200.00 reversal.

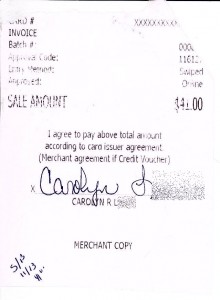

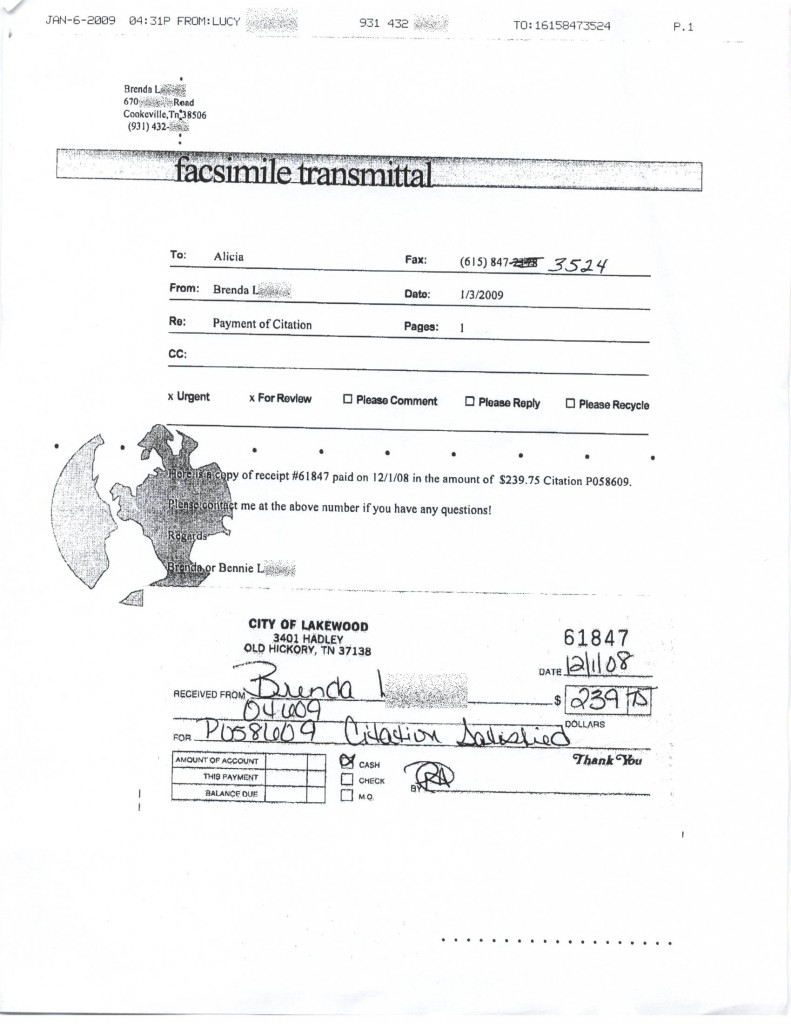

Initially, the recorder and I thought that the most likely scenario was that the court clerk had used her own card and just did not have sufficient available credit. We were wrong. The recorder, working with the processing bank, deduced that the reason that the card had been declined was that it had been reported lost. As she followed the clues, she determined that the card belonged to an individual who had used it to pay for a traffic violation at city hall and left it there. The recorder found the citation and receipt filed with paid tickets. She also found the other piece to the “puzzle” that was the scrap of receipt that the court clerk had attached to Brenda L.’s citation (right).

Several months later, the water clerk found the credit card and credit slip (from the reversal) in a box of labels. When the former court clerk was still employed by the city, the labels were in a supply closet at the opposite end of the building from her office.

Several months later, the water clerk found the credit card and credit slip (from the reversal) in a box of labels. When the former court clerk was still employed by the city, the labels were in a supply closet at the opposite end of the building from her office.

Other Altered Records

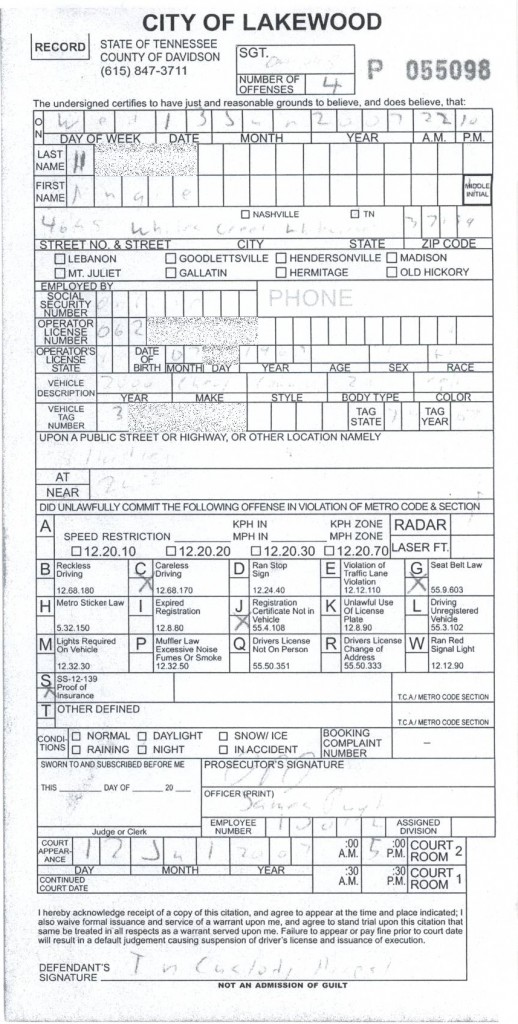

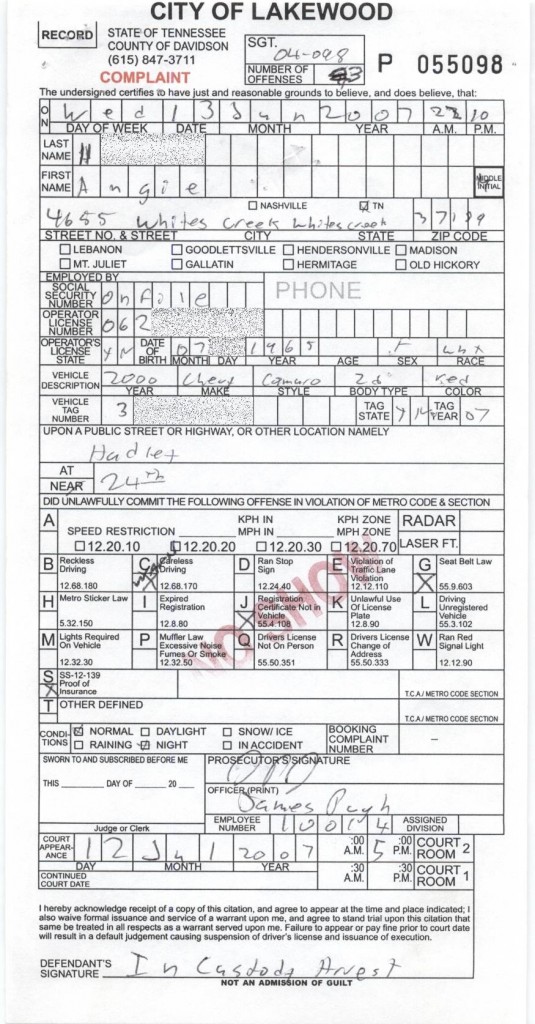

I found the citation pictured below in the paid ticket files.

I thought it was strange that an officer would arrest an individual, but change a careless driving violation to a warning! Fortunately, the officer had his own copy.

I thought it was strange that an officer would arrest an individual, but change a careless driving violation to a warning! Fortunately, the officer had his own copy.

Procedures and Results

Having discovered that the court clerk used several different methods of altering or omitting records to conceal theft from city court collections, I began to examine the records from the entire period of her employment. First, I re-footed each batch of receipts to determine if the totals for cash (coins and currency only, as used here) and checks were identical to those found on deposit slips (as described in the previous post). In all, the former court clerk exchanged $3,953.00 of checks for cash that she had taken from collections.

After that, I examined the city’s copies of the receipts in more detail. The bookkeeper’s work is included in this category. In all, $7,126.00 of theft was concealed by short and altered receipts.

Not surprisingly, there was evidence that the then-court clerk concealed theft by other means. The recorder examined the contents of the paper shredder in the clerk’s office, shortly after the clerk was suspended. She found evidence of several court documents being shredded, including receipts. She found the intact receipt number shown in the picture on the right. The city purchased receipts that were numbered sequentially and used the books in order. The receipt number shown was from the last book, which would not have been used for some time. There was enough evidence to attribute an additional theft of $344.50 to receipts that were issued from this book, which neither the recorder nor the bookkeeper was aware of.

In all, the available records indicated theft of $11,423.50.

In addition to the systematic theft that the former court clerk pled to, one entire $497.25 deposit from the summer of 2008 was stolen. This crime is officially unsolved and I have not included it in the total theft attributed to the former court clerk.. The reader should note that theft of over $500.00 is a class E felony in Tennessee. Since this was just under $500.00, it would have been a misdemeanor, had anybody been charged.

Over the entire nearly three-year period, net cash short or over (not attributable to any specific transaction) was a shortage of $328.33.

Including cash short or over and the missing deposit raised the total that could not be accounted for to $12,249.08.

Lessons

Lakewood had a greater degree of oversight than several small cities and towns that I have audited. However, the bookkeeper always looked at the same things, at least until the credit card payments went online. In fact, it was the changes necessitated by the new payment method that led to the Brenda L. transaction.

On a day-to-day basis, the city could have had better segregation of duties. Unlike the one-person offices that the Division of Municipal Audit often encounters, the city had a court clerk, water clerk, and recorder in the business office. The court clerk was able to falsify all of the supporting documents to conceal the missing collections.

During the clerk’s period of employment, she neglected to update the court records for several of the individuals that had checks substituted for stolen cash in bank deposits. The court clerk’s office had correspondence with several effected drivers; the recorder said that she remembered others. At the time, all of these were attributed to mistakes and not investigated in more depth.