One of the most interesting investigative audits that I performed substantial work on was the 2009 audit of the City of Lakewood. The Division of Municipal Audit’s report is here. Related exhibits, which are court documents from the case are here.

Municipal Audit Background

Since this is the first case that I have written about, here is some background about who I work for, what we do, and how we present it.

The Division of Municipal Audit operates withing the Office of the Comptroller of the Treasury (URL = http://comptroller.state.tn.us) of the State of Tennessee (URL = http://tn.gov). The Division of Municipal Audit oversees the audits of cities, utility districts, school activity funds, certain non-profits that receive state funding, and now school support organizations (mostly parent-teacher organizations and booster clubs). Several members of the Municipal Audit staff oversee the annual financial audits that most of the entities are legally require to have. Mostly, these audits are performed by private CPA firms under contract.

The other function of the division is to investigate allegations of fraud, waste, and abuse. I have been a member of the investigative audit staff since 2001, when I was hired.

Information about the cases that we investigate comes to the office through several channels. The contract that the various municipal entities and CPA firms enter includes a mandate that the firm will report any suspected instance of fraud that its procedures reveal. Since 2007, municipal officials have been legally required to report all known instances of fraud to the comptroller’s office. Other investigations begin at the request of a district attorney general. Some cases begin based on reports from citizens, either through hotline calls or by calling or writing directly to the division. Despite all of these channels, occasionally the division’s management will first learn about an allegation from a report in the news media.

The Division of Municipal Audit almost always issues a public report when an investigative audit is complete. Occasionally, when an investigation is done at the request of a DA, the end product will be a letter to that DA that is not a public document. The other exception is the rare occasion when there is essentially nothing to report beyond information that was in the entity’s last annual report.

Case Background

The City of Lakewood was a small city at the eastern edge of Metropolitan Davidson County. Without going into extensive detail, in the 1960s, when the City of Nashville and Davidson County consolidated their governments, a few smaller towns within the county decided to retain their status as separate municipalities.

My use of the past tense in the preceding paragraph was deliberate. A group of residents petitioned to have a referendum placed on the August 2010 ballot that, if approved, the City of Lakewood would surrender its charter and join Metro Nashville. The measure passed, but only by a handful of votes. Lakewood City Government successfully challenged the result on the basis of procedural mistakes during early voting. The measure was presented again during a special election in the spring of 2011. It passed again and the result stood. As I write this, on June 10, 2011, WTVF still has a link to a story about Lakewood’s final day (there are links to stories about the earlier election on that page). The Lakewood Website is still active as of today.

The Case

On January 5, 2009, the Division of Municipal Audit received a report that the Lakewood City Court clerk had apparently stolen $200.00. I was instructed to be at Lakewood City Hall the next day to evaluate the situation.

The investigative audit team consists of two audit managers and usually about six staff auditors. Due to the downturn in the economy, state budgets have been tight. Considering the number of entities for which the Division of Municipal Audit is responsible, the number of experienced staff available, and budgetary constraints, some cases have to be referred back to the entity or to the contract auditors, with explicit instructions to keep the division informed about anything else that is subsequently discovered. On that first day, if I had not found anything questionable beyond the $200 that had been reported, we probably would not have pursued the case. With that in mind, I described my procedures to the city employees that were present throughout that first day, in case they had to conduct an investigation internally. Our standard procedure is generally to reveal as little as possible and to be highly cautious about relying upon client-prepared working papers.

The First $200

The city manager and recorder explained that the discrepancy was in a credit card transaction. The city had only been accepting credit card payments for about two months. In addition to the full-time city staff, which included the recorder, the court clerk, and a water clerk who accepted court payments when the court clerk was unavailable, the city had a part-time bookkeeper who verified that the amounts collected, as recorded on manual receipts, traced to deposit in the city’s bank account. This part-time bookkeeper realized that there was no oversight for the credit card transactions.

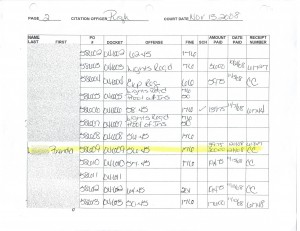

The bookkeeper found that a larger amount had been recorded for credit card p ayments on the court dockets than the city had received in electronic deposits. She attempted to gather additional information, in case she had to ask the bank to locate missing electronic deposits. The transaction that stuck out was on this docket. Brenda L. appeared to have paid $200 using a credit card and paid the balance in cash.

ayments on the court dockets than the city had received in electronic deposits. She attempted to gather additional information, in case she had to ask the bank to locate missing electronic deposits. The transaction that stuck out was on this docket. Brenda L. appeared to have paid $200 using a credit card and paid the balance in cash.

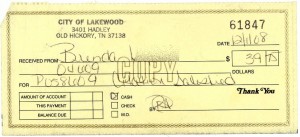

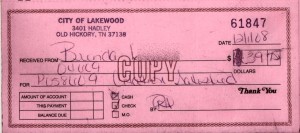

Lakewood used manual 3-part receipts. The person that remitted payment received the original copy, the yellow (middle) copy was attached to the paid citation, the pink (third) copy was to remain in the spiral-bound receipt book.

The bookkeeper pulled the citation from the file. Attached, she found the yellow copy of receipt 61847, which was consistent with the information on the docket. She also found a small scrap of a credit card charge slip, which contained almost no useful information.

The pink copy also showed $39.75 cash paid, but it had a mark where the 100s digit would be, as if it had been changed.

At that point, the recorder asked the court clerk to find the remainder of the torn credit card charge slip. At that point, the court clerk was left alone in her office, ostensibly to search.

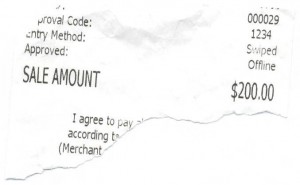

After some time had passed, the court clerk returned with another scrap, which showed a $200 credit card payment.

The recorder was skeptical. Surprisingly, the court clerk offered to call the individual who had been issued the citation, Brenda L. Brenda L responded that she had paid entirely in cash. She still had the receipt and would be willing to fax it to Lakewood City Hall.

Next Post…

I will show the fax of Brenda L.’s receipt and discuss the magnitude of the theft.

I just want to mention I am beginner to blogging and site-building and honestly liked your web site. Likely I’m likely to bookmark your website . You actually come with awesome well written articles. Appreciate it for revealing your blog site.